Russian Baddies

Perhaps the modern meanie has assumed the persona of the Hollywood bad guy

I was born in the early eighties, somewhere between Brezhnev and Andropov, when the Cold War was so insane that Star Wars was on the cards, and heightened tensions between the two empires had established a critical mass in proxy wars across Latin America, Asia, Africa and throughout the second and third world. Ronald Reagan had come into power with his famous “Evil Empire speech”, opening up the Western imagination.

Hollywood had been no stranger to framing Russians in the arts, honing its craft in the McCarthyist period and getting better throughout the 60s and 70s, but it wasn’t until the eighties that the formula found a place in Reagan’s America. With the purging of all the communist directors and bleeding-heart filmmakers from Hollywood, the eighties cleared the way for action blockbusters that took the experience to new levels. This was the period that the early millennials first experienced the arts, and for a young boy with older cousins who liked pro-wrestling, these action blockbusters were like manna from heaven.

Anyone my age knew someone that had the good VHS collection, and my cousins Nick and John had that hallowed trove of Hollywood violence. When I first watched Arnold Schwarzenegger as Dutch, throwing machetes and firing under-barrel grenade launchers at Sandinista-style paramilitaries in some nondescript part of the central American jungle, I had no idea of the context that my hero was chopping through with large calibre machine guns. But I thought it was fucking awesome.

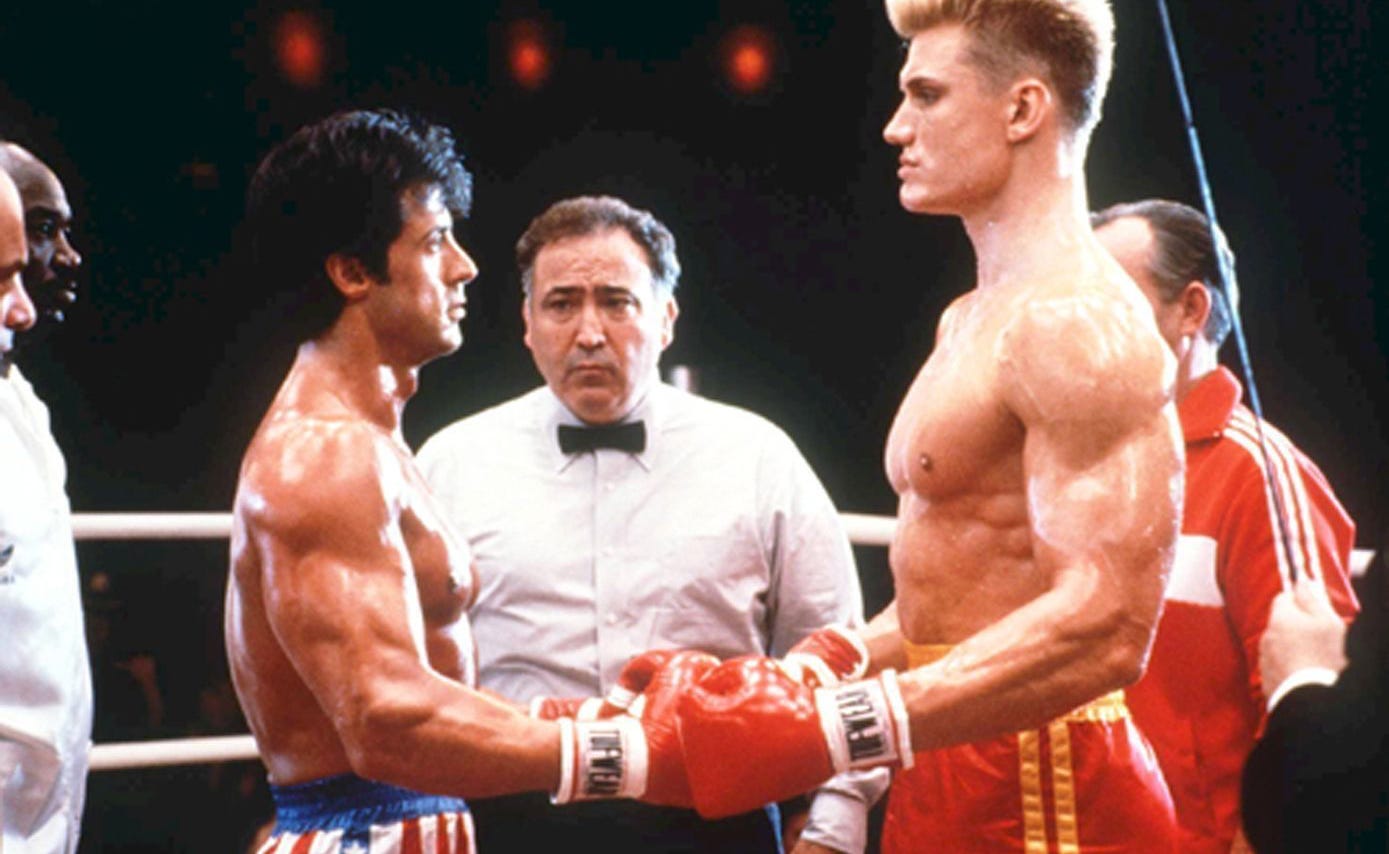

In the seventies, Rambo: First Blood started the franchise off as an anti-war film about the damage and suffering of returning Vietnam veterans, but by the eighties, it had become the movie poster for the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan. And while John Rambo got emotional consoling with Bin Laden’s Mujahedeen about the horrors of war in his third instalment before shrugging off their heartfelt concerns and knocking off the Russian brass in the final act, Rocky Balboa was throwing his weight on the cracking iron curtain, leaving his home in Philadelphia to train in the blizzards, chopping wood and trudging through the tundra, while Ivan Drago got to train at some space centre.

By the time Dolph Lungren was knocked down by Russia in front of the entire Soviet politburo and military brass, as Rocky got the nod from Gorbachev in the crowd followed by the rapturous applause, by the time Rambo IIIs explosive arrow took out the last Soviet chopper, the Western world had well and truly perfected the art of the Russian bad guy. The space age training centres wouldn’t represent anything near the truth in the Perestroika-riddled Soviet Union, and the evil Russian soldier returning from Rambo III’s Afghanistan would return to a country in economic and ideological peril. He probably wouldn’t get his pension, and the USSR wouldn’t make it to see Rocky V.

After Perestroika ceded to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev moved onto Pizza Hut ads, Yeltsin turned the new Russian Federation into a pariah, but the Russian remained the bad guy in film and television.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, tectonic friction of ideological spheres of influence softened into a unipolar world led by the United States, and the imagination of Hollywood stretched out into the world it ruled over to find new baddies. With a few years to breathe after the Iraq war, and the iron curtain well and truly melted, 1994 was a year that demonstrated a new crop of bad guys that represented the ‘end of history’ feel that Hollywood was going for. Gone were the bad guys working for big evil agendas, in were the bad guys that represented the terrorism, the drug dealers and the jaded former nemisis who hate the system. All that remained were the remnants of opposition and the obstacles to Hollywood’s hegemony.

True Lies was one of my favourite films from this landmark era, another Schwarzenegger thrill ride directed by legendary director James Cameron. Before I saw that film I had no idea what an Arab terrorist was, or what they would possibly be fighting for, but after their depiction in this five star thrill ride, it didn’t really matter, because they were the best bad guys ever. After the Cold War, the films were showing us how to hate on a whole new group of unsavoury characters, with a whole new group of objectives.

In the nineties, jaded former soviets would hijack Harrison Ford’s plane in Airforce One, or the same actor would take out Columbian Drug lords in films like ‘Clear and Present Danger’, and the Tom Clancy era of American exceptionalism took hold. Later, exotic global backdrops became playgrounds for CIA assets that seemed to be able to act with impunity, and Jack Ryan turned into Jason Bourne, and the grey areas expanded. But then, Hollywood got some more material just in time. The War on Terror age of action film making began.

This age lasted more than a decade and perhaps had some of the poorer action films in the history of cinema. Gone were the shameless blasting of Guatemalans under Jessie Ventura’s minigun, now Hollywood had to offer a moral justification for doing so. The simplicity of lobbing quad rocket launchers into remote jungle bases was replaced by the complexity of political narratives interwoven into muddy plotlines. Arabs, Somalis, Burmese and Latin Americans started populating the kill counts of Hollywood action scenes, along with deep state intrigue and ultra-sophistication. The Russian enemy never walked out of the scene in all of this, going from evil Soviet Colonel to evil and jaded Ex-Soviet Colonel.

By the time I was watching these films in the late eighties, the war was pretty much over, and I didn’t quite understand it. Dutch and Rambo, Red Dawn and Toy Soldiers, all these shitty jingoistic eighties action films came to define me and an entire generation, but by the time we played the video games, we were complicit in the whole thing in ways we couldn’t understand.

As the digital realm captured my teenage imagination in the late nineties, the Russians were also the bad guy of choice for the burgeoning industry of video games. In the 30-year history of first person shooter video games, from story driven narrative experiences to open world sandbox multiplayer experiences, dead Russians have been the staple polygon ragdoll of choice to shoot, maim, explode and teabag. And main choice of the monsters that commit the unspeakable.

Perhaps all the bad guys from the movies and video games have had an impact on the way we view conflict between nations. The loud and unreasonable Somali Pirate, the desperate Arab terrorist, the Chinese overlord, the cold South American guerrilla and the brutality of the Russian, could the pipeline of Hollywood stereotype have a way of seeing the way we view the bad guys? And the way we see ourselves?

As the west looks to Russia with more intensity over the conflict with Ukraine, has the ‘Evil Empire’ Ivan Drago, Red Dawn, The Manchurian Candidate, and films like Rambo III influenced what lens we view it through? Has ‘Reds under the bed’ and nineties Harrison Ford and making false equivalencies between Putin and Hitler, have these things had any bearing on our views on realpolitik?

Although we may wish to see things with the clarity of a Hollywood stereotype, things are never so simple. Especially in global conflict. The caricature of a bad guy serves its purpose to dehumanise the opponent of the protagonist but can do little to unravel the reasoning behind the fight in the first place, and can obstruct the pathway to resolution. Ultimately, everyone might be more confused than when we started.